PolyUFC: Polyhedral Compilation Meets Roofline Analysis for Uncore Frequency Capping

Nilesh Rajendra Shah, M V V S Manoj Kumar, Dhairya Baxi, and Ramakrishna Upadrasta

Published in CGO’26

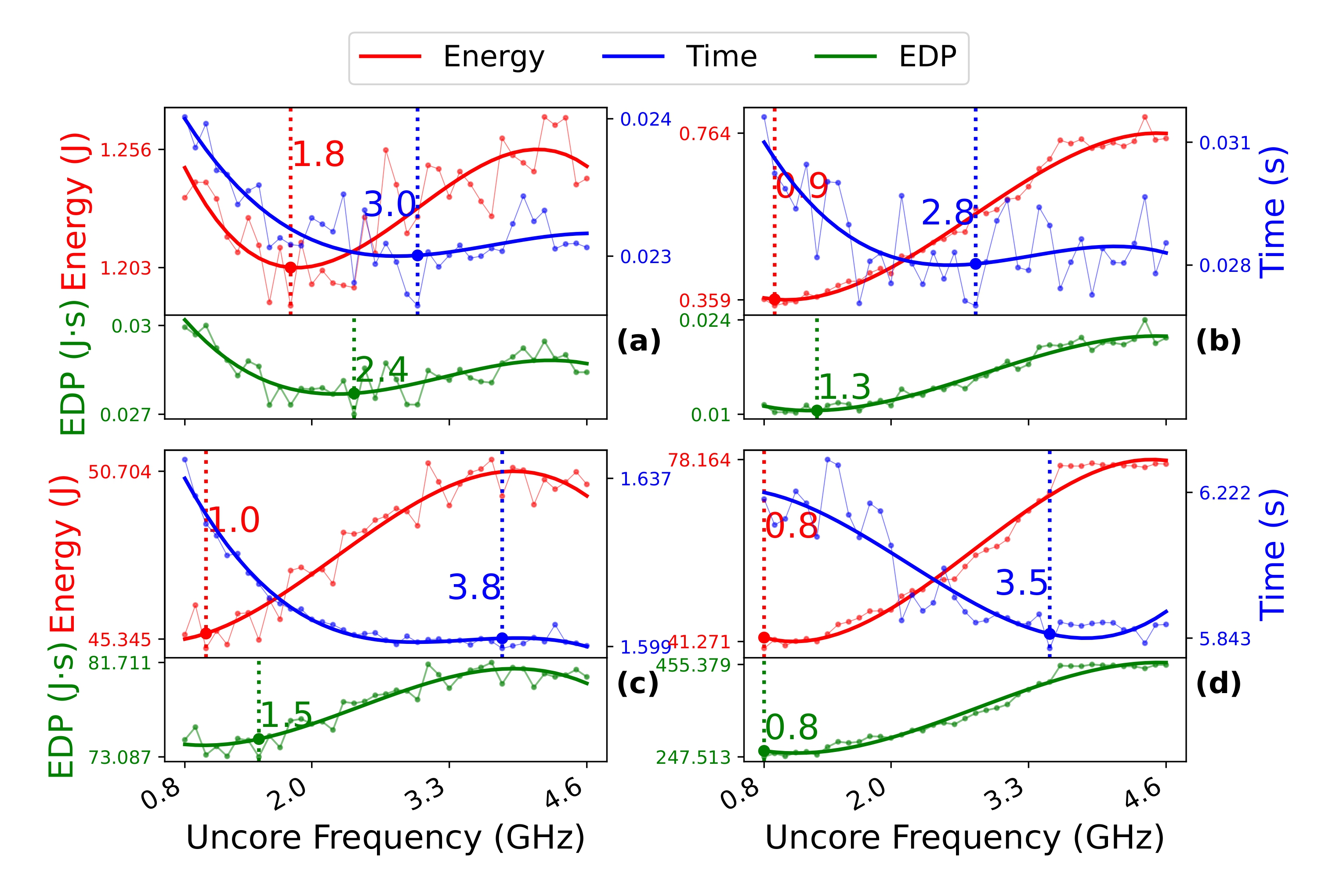

Fig. 1.

Scaling and Capping comparison across the uncore frequency range.

(a)

Fig. 1.

Scaling and Capping comparison across the uncore frequency range.

(a) gemver capped from PolyBench.

(b) gemver frequency scaled.

(c) conv2d from ConvNeXt capped.

(d) conv2d scaled.

APPENDIX

In App. A, we show the variables used for mathematical modeling in Sec. 2. In App. B, we show a study comparing frequency capping and scaling. We also discuss the experiments that we performed to obtain the (performance and power) rooflines, followed by a pointer-chasing algorithm for miss penalty. 1

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| \(T^{\Omega}_{\mathcal{I}}\) | Total time taken for floating point operations |

| \(T^{Q}_{f_c,\mathcal{I}}\) | Total time taken for memory operations with \(f_c\) and \(\mathcal{I}\) as parameters |

| \(\Omega\) | Total number of floating point operations |

| \(Q_{\text{DRAM}}\) | Total number of bytes transferred between \(LLC \leftrightarrow DRAM\) |

| \(\widehat{P}_{f_c,\text{DRAM}}\) | Peak power per byte transfer between \(LLC \leftrightarrow DRAM\) |

| \(P^{\text{core}}_{\mathcal{I}},\; P^{\text{uncore}}_{f_c,\mathcal{I}}\) | Total power consumption of the core and uncore |

| \(P_{f_c,\mathcal{I}}\) | Total power consumption of the package |

| \(f_c\) | Frequency cap of the uncore |

| \(\rho^{h}_{c_i},\; \rho^{m}_{c_i}\) | Hit/Miss ratio of cache level \(i\) \((1 \le i \le N)\) |

| \(\mathcal{H}_{c_i}\) | Hit time to access data in cache level \(i\) |

| \(\mathcal{M}^{t}_{f_c,LLC},\; \mathcal{M}^{p}_{f_c,LLC}\) | Miss time and power to access data in cache level \(LLC\) |

Table I. Variables and their descriptions.

B. Frequency scaling vs. capping

To understand the difference between uncore frequency scaling and uncore capping, we compare both optimization techniques. In Fig. 1, when setting the uncore frequency, we limit the maximum uncore frequency for capping the uncore component, compared to frequency scaling which fixes the uncore frequency for the entire runtime of the program. We compare the scaled and capped versions of conv2d and gemver to understand the differences. It can be seen that frequency capping provides more fine-grained control over the frequency range and reduces latencies due to frequency changes. Therefore, for improving performance, frequency capping is preferable when compared to scaling using a compiler-generated frequency control. For conv2d, capping achieves \(5.72\times\) better performance than scaling over the uncore frequency range. However, for energy-specific improvements, scaling is a viable option with up to \(11\%\) more energy improvement over capping.

TABLE II

Selected kernels from PolyBench [6] with performance characterization on BDW and RPL (static vs dynamic).

| Kernels | BDW | RPL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PolyUFC | HW | PolyUFC | HW | |

| 2mm | CB | CB | CB | CB |

| 3mm | CB | CB | CB | CB |

| atax | BB | BB | BB | BB |

| bicg | BB | BB | BB | BB |

| gemm | CB | CB | CB | CB |

| gemver | BB | BB | BB | BB |

| gesummv | BB | BB | BB | BB |

| mvt | BB | BB | BB | BB |

| syr2k | BB | CB | CB | CB |

| syrk | CB | CB | CB | CB |

| doitgen | CB | CB | CB | CB |

| correlation | CB | CB | CB | CB |

| floyd-warshall | BB | BB | BB | BB |

| deriche | BB | BB | BB | BB |

| adi | BB | BB | BB | BB |

| jacobi-1d | CB | CB | CB | CB |

| trmm | CB | CB | CB | CB |

| trisolv | BB | BB | BB | BB |

| cholesky | CB | CB | CB | CB |

| lu | CB | BB | CB | CB |

| durbin | CB | CB | CB | CB |

| gramschmidt | CB | BB | CB | CB |

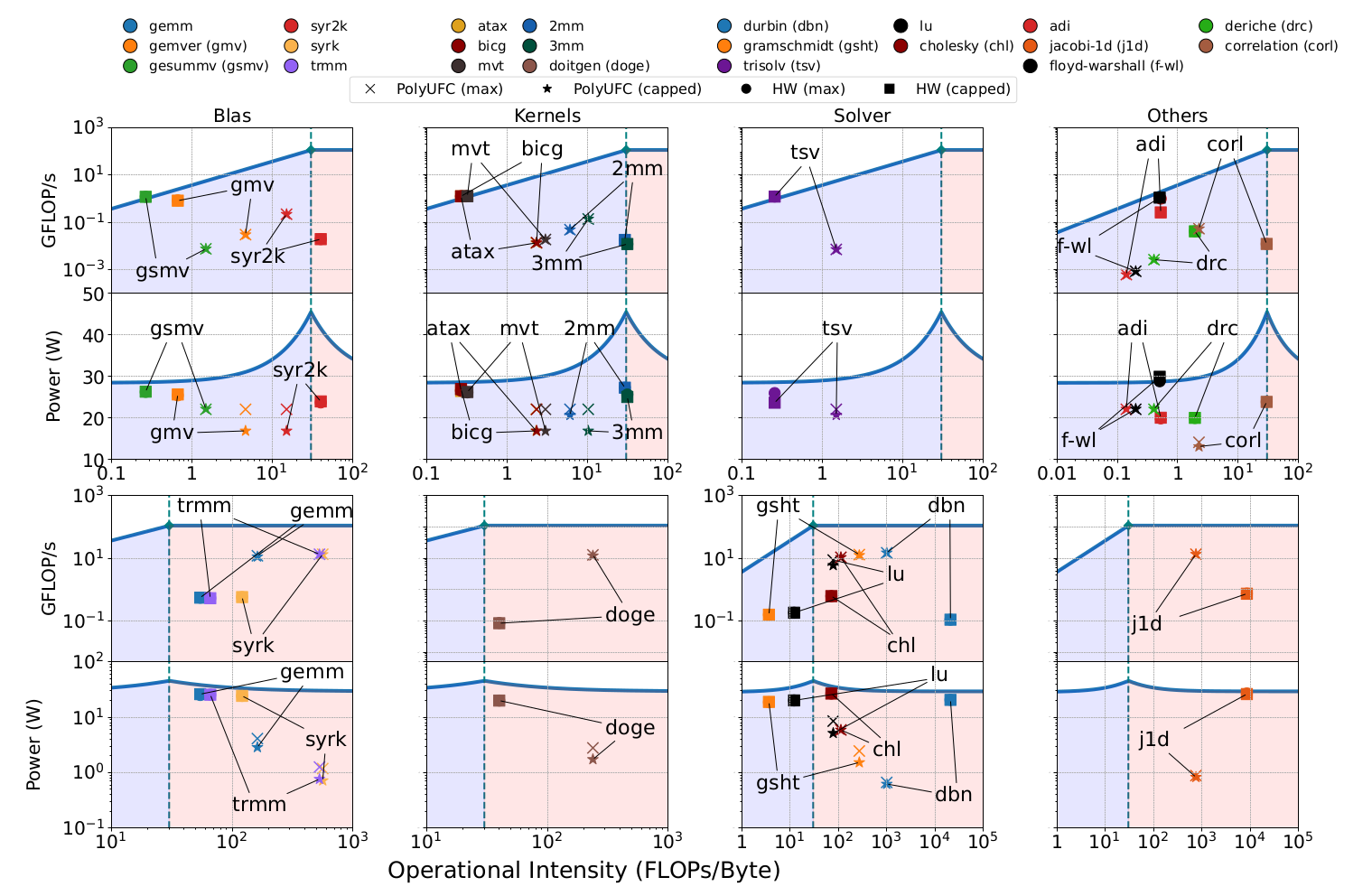

C. Kernel Characterization

In Fig. 2, we show the kernel characterization for BDW. PolyUFC correctly characterizes PolyBench [6] codes on large problem sizes for 20 out of 22 kernels that compile within the timeout limit of 30 minutes or are parallelized using Polygeist [7] with the Pluto optimizer. In Table II, we show the performance characterization accuracy for PolyBench kernels on BDW and RPL.

Fig. 2. Performance and Power Characterization on BDW for PolyBench with large problem size. Vertically, from top to bottom, the characterization of programs shifts from BB → CB due to higher OI.

D. Experimental Setup and Other Details

a) Performance counters. In Table III, we show the set of events used to collect hardware measurements for OI calculations on BDW and RPL.

b) Hardware prefetchers and vectorization. For all experiments, hardware prefetchers and loop vectorization are enabled (default -O3). However, we do not explicitly model prefetchers, as we assume that their impact on uncore and DRAM characterization remains unchanged. While vectorization is enabled during compilation, it does not directly affect the uncore frequency search for energy improvements.

TABLE III

Common PAPI and native events for estimating FLOPs and cache misses. Availability is architecture-dependent; added from papi_native_avail.

| Category / Description | Event |

|---|---|

| FLOPs SP (BDW) | FP_ARITH_INST_RETIRED:SCALAR |

| FLOPs DP (BDW) | FP_ARITH_INST_RETIRED:SCALAR_DOUBLE |

| FLOPs SP (RPL P-core) | adl_glc::FP_ARITH_INST_RETIRED:SCALAR |

| FLOPs DP (RPL P-core) | adl_glc::FP_ARITH_INST_RETIRED:SCALAR_DOUBLE |

| FLOPs SP (RPL E-core) | adl_grt::FP_ARITH_INST_RETIRED:SCALAR |

| FLOPs DP (RPL E-core) | adl_grt::FP_ARITH_INST_RETIRED:SCALAR_DOUBLE |

| LLC misses | PAPI_L3_TCM or perf::PERF_COUNT_HW_CACHE_LL:MISS |

c) Turbo boost. In the experimental setup, we enable turbo boost technologies for the core when applying frequency caps for the uncore component.

d) Obtaining rooflines. We generate comprehensive rooflines—both performance and energy—spanning the entire frequency spectrum available on each platform. We begin from CPU-specific microbenchmarks [8] derived from the original roofline [9] and energy roofline models [10]. We retargeted these microbenchmarks for recent Intel processors with enhanced memory subsystems that include two different port configurations: 2-Load/2-Store (Intel Cypress Cove: RKL) and 3-Load/2-Store (Intel Raptor Cove: RPL) [11].

e) Roofline microbenchmarking. The OpenMP-based microbenchmarks require approximately \(\approx 3\) seconds per iteration when executed at fixed core and uncore frequencies on RPL. We generate microbenchmarks [8,12] for intensities ranging from \(0\;–\;10^6\), and each PAPI event runs for \(2^{10}\) iterations, for a total wall-clock time of approximately \(\approx 1\) hour.

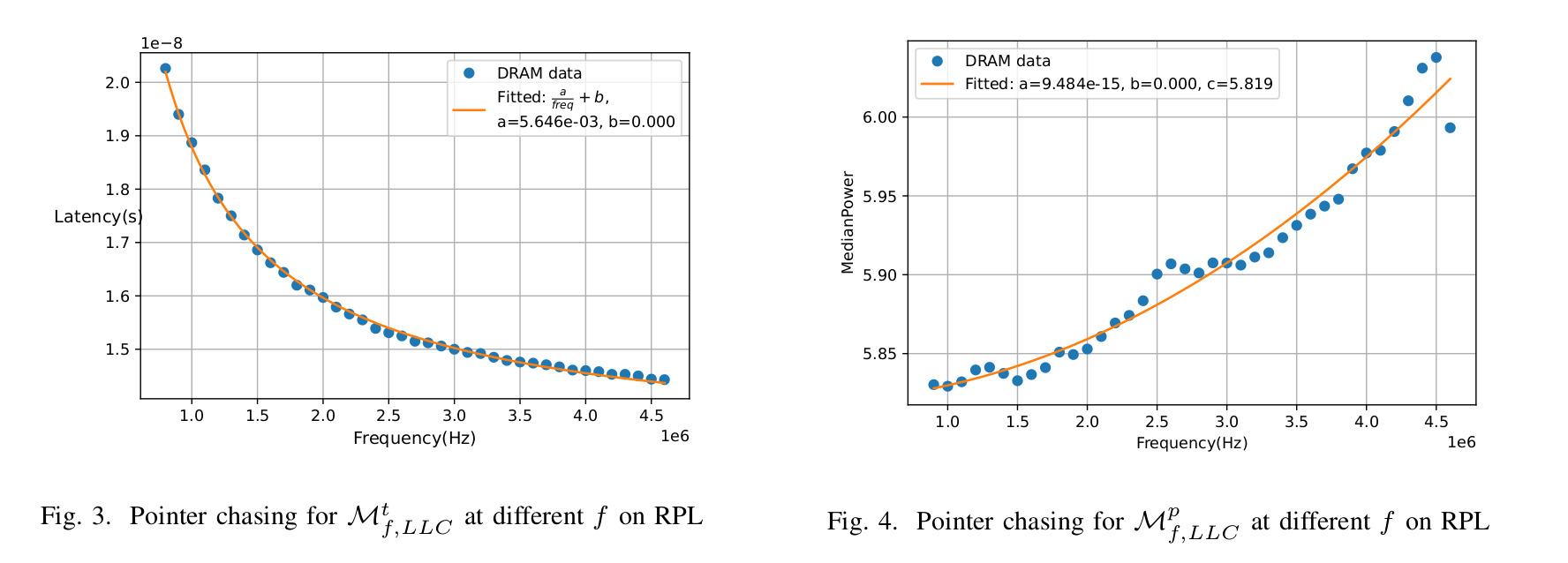

f) Computing miss-penalty with pointer-chasing. To obtain average memory latency across the memory hierarchies, the hit latency and miss penalty for different memory levels are required. To obtain these latencies, we use random cache-access microbenchmarks using pointer-chasing threads [8]. Our measurements eliminate the effect of prefetching and parallelism in latency calculations.

g) Curve fitting on miss penalty. For analytical modeling over the uncore component, we use non-linear curve fitting on the space of uncore frequencies to obtain \(\mathcal{M}^{t}_{f,LLC}\) and \(\mathcal{M}^{p}_{f,LLC}\) with (f) as a parameter. For example, on the RPL platform in Fig. 3, we show the curve fitting over a range of uncore frequencies for miss latency using Eq. (6).

Go to Main Page:

REFERENCES

[1] A. Abel and J. Reineke, “nanobench: A low-overhead tool for running microbenchmarks on x86 systems,” in 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Performance Analysis of Systems and Software (ISPASS). IEEE, 2020, pp. 34–46.

[2] J. W. Choi, “A roofline model of energy ubenchmarks,” https://github.com/jeewhanchoi/a-roofline-model-of-energy-ubenchmarks , 2020.

[3] J. W. Choi, D. Bedard, R. Fowler, and R. Vuduc, “A roofline model of energy,” in 2013 IEEE 27th International Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Processing, 2013, pp. 661–672.

[4] Intel Corporation, “Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual,” https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/developer/articles/technical/intel-sdm.html ; https://cdrdv2.intel.com/v1/dl/getContent/671200 , 2025.

[5] W. S. Moses, L. Chelini, R. Zhao, and O. Zinenko, “Polygeist: Raising C to polyhedral MLIR,” in 2021 30th International Conference on Parallel Architectures and Compilation Techniques (PACT). IEEE Computer Society, Sep. 2021, pp. 45–59.

[6] L.-N. Pouchet et al., “PolyBench benchmarks,” http://sourceforge.net/projects/polybench/ , 2025.

[7] S. Williams, A. Waterman, and D. Patterson, “Roofline: An insightful visual performance model for multicore architectures,” Commun. ACM, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 65–76, Apr. 2009. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1145/1498765.1498785